Read our expert review on the management of growth and complications for children with achondroplasia.

Achondroplasia is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by a gain-of-function fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) mutation (most often p.Gly380Arg), leading to impaired endochondral ossification and bone growth through excessive RAS–MAPK pathway activation. It affects approximately 1 in 25,000–35,000 individuals, with 80% of cases occurring sporadically. Diagnosis is typically made in infancy based on characteristic clinical features (rhizomelic limb shortening, frontal bossing, macrocephaly, midface hypoplasia, and trident hands) and radiological findings (including reduced interpeduncular distance, narrow sacrosciatic notches, and short square ilia)[1]. This review examines the clinical complications of achondroplasia in children, with a focus on growth and emerging treatments that are expected to significantly change management in the near future.

International consensus guidance exists for the monitoring, investigation and management of the medical complications of achondroplasia across the childhood lifespan [2], of which the most common/significant are briefly discussed here:

Sleep apnoea

Sleep disordered breathing can affect children with achondroplasia (most commonly in infancy and young childhood) in 50–80% of cases. Sleep study or polysomnography can detect asymptomatic cases and should be requested routinely in infancy.

Foramen magnum stenosis

Approximately 36% of children with achondroplasia develop flattening of the cervical cord without signal change and 14% critical stenosis of the foramen magnum, usually by the age of 3 years. Developmental delay and motor regression are suggestive of this clinically. MRI is the investigation of choice for monitoring and should be undertaken within the first 3–6 months of life [3].

Spine

Up to 90% of infants with achondroplasia are born with a thoracolumbar kyphosis, although most resolve spontaneously. Later in childhood, most children will develop a lumbar hyperlordosis. Both of these issues have the potential to result in spinal stenosis, which needs monitoring through clinical signs and symptoms of neurological deficit [1].

Genu varum

Genu varum will develop in 40–70% during childhood years, along with tibial torsion and recurvatum, which causes pain and mobility issues. Hemiepiphysiodesis is the surgical management of choice, if the growth plates are open [4].

Middle ear dysfunction

Chronic otitis media and conductive hearing loss are common in early childhood, requiring regular hearing checks and grommets as needed.

Obesity

Obesity is well-recognised in childhood and young adulthood and can worsen respiratory and orthopaedic issues. Monitoring with growth measurements and advice on healthy lifestyle measures are important to avoid long-term cardiometabolic risk.

Children with achondroplasia have slowed growth and no significant puberty-related growth spurt, resulting in an adult height of 115–140 cm [1]. Area-specific achondroplasia growth charts can be used to monitor progress. The short stature and body disproportion can affect daily functioning and quality of life.

Recombinant growth hormone may temporarily increase growth velocity in the first 2 years [5] but may not significantly impact final adult height, so it is rarely used in practice [6]. Surgical limb lengthening remains an option to increase height but carries a high risk of complications and requires thorough family counselling.

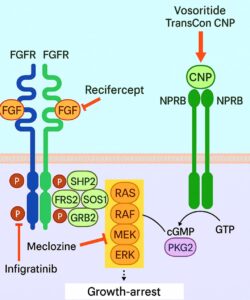

More recently, targeted treatments have been developed specifically for achondroplasia. Figure 1 summarises the targets of these.

Vosoritide, a C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) analogue, delivered by once daily subcutaneous injection, inhibits signalling downstream of FGFR3, via a parallel pathway. A phase 3, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre, 52-week trial in children aged 5–18 years demonstrated safety and a mean improvement in annualised growth velocity (AGV) of 1.57 cm/year [7]. Open-label extension and longer-term follow-up studies have demonstrated ongoing safety and sustained growth promotion for up to 6 years, with significant improvements in the upper-to-lower body segment ratio [8, 9]. This has led to its approval for use in clinical practice in children with achondroplasia in some parts of the world [10, 11], although not yet in the UK. Recent international consensus guidance exists for the implementation and monitoring of vosoritide [12].

Navepegritide (TransconCNP) is a once-weekly subcutaneous CNP analogue that has more recently demonstrated safety and efficacy in a phase 2, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, 52-week dose-finding trial in children with achondroplasia aged 2–10 years [13]. The highest doses demonstrated a significant improvement in mean AGV compared with placebo (5.42 vs 4.35 cm/year).

Infigratinib is a daily oral FGFR1–3-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. In a multicentre, dose-finding study in children aged 3–11 years, infigratinib was shown to be safe, with the maximal dose demonstrating a significant improvement after 18 months in mean AGV (2.5 cm/year) and mean height z-score (0.54) relative to a reference group [14].

Other potential therapies, which are in an early-phase development include the motion sickness agent meclozine (downstream RAS–ERK pathway inhibitor), although research into recifercept (soluble FGFR3) has now been terminated [15].

Crucially, data are still awaited as to whether any of the above drugs can impact on the other serious medical complications of achondroplasia, beyond their growth effects.

Figure 1. Treatment Strategies for Achondroplasia. Activation of FGFR3 begins when FGF ligands bind to and induce dimerisation of the receptor, triggering transphosphorylation (P) of its intracellular kinase domain. This leads to recruitment of adaptor proteins (FRS2, SHP2, and GRB2), which in turn enable SOS1 to activate RAS and initiate the downstream RAS–ERK signalling cascade, which causes growth arrest in achondroplasia. Current therapeutic approaches under clinical evaluation for achondroplasia are designed to reduce FGFR3 signalling through multiple mechanisms. These include: Recifercept, which acts as a decoy receptor to neutralize FGF ligands; Infigratinib, which inhibits the kinase activity of FGFR3; Meclozine, which directly suppresses the RAS–ERK signalling pathway. In contrast, TransCon CNP and Vosoritide operate via the CNP signalling pathway, counteracting FGFR3 signalling by promoting PKG2-dependent inhibitory phosphorylation of RAF, thereby attenuating downstream effects of the FGFR3 pathway. Figure generated with the assistance of artificial intelligence (ChatGPT).