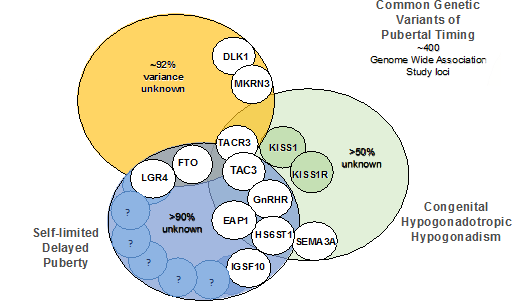

Delayed puberty (DP) is common in the developed world, affecting over 2% of adolescents, and is associated with adverse health outcomes including short stature, reduced bone mineral density and compromised psychosocial health. The majority of patients have constitutional or self-limited DP, which is often familial, most commonly segregating in an autosomal dominant pattern. However, the key genetic regulators in self-limited DP are largely unknown [1], Figure 1.

Delayed puberty (DP) is common in the developed world, affecting over 2% of adolescents, and is associated with adverse health outcomes including short stature, reduced bone mineral density and compromised psychosocial health. The majority of patients have constitutional or self-limited DP, which is often familial, most commonly segregating in an autosomal dominant pattern. However, the key genetic regulators in self-limited DP are largely unknown [1], Figure 1.

Insights into the genetic mutations that lead to familial DP have come from sequencing genes within the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pathway known to cause pubertal failure. Recently, via next generation sequencing, mutations in HS6ST1, GNRHR, IL17RD, SEMA3A, TACR3 and TAC3 [2] have been found in patients with DP and spontaneous onset of puberty. One persuasive hypothesis is that a single deleterious mutation may lead to a phenotype of DP, whilst two or more mutations may be required to cause absent puberty, for example in congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (cHH).

By extension, other pathways related to GnRH neuronal development and function have been explored in the search for the genetic basis of DP. Mutations in IGSF10 provoke a dysregulation of GnRH neuronal migration during embryonic development, which first presents in adolescence as DP without previous constitutional delay in growth [3]. Pathogenic IGSF10 mutations leading to disrupted IGSF10 signalling potentially result in reduced numbers or mistimed arrival of GnRH neurons at the hypothalamus; this produces a functional defect in the GnRH neuroendocrine network and thus an increased “threshold” for the onset of puberty.

Upstream transcriptional regulators of GnRH signalling, such as KISS1, OCT2, TTF1, YY1 and EAP1, which act as a pubertal “brake” through a balance of activating and repressive inputs, have been proposed as attractive candidates for the pathogenesis of DP. EAP1 is known to contribute to the initiation of female puberty through transactivation of the GnRH promoter, and mutations in EAP1 have very recently been found in families with self-limited DP [4]. New evidence has also identified small non-coding RNAs important for the murine critical period (or mini-puberty). The microRNA (miR)-200/429 family and miR-155 both act as epigenetic up-regulators of GnRH transcription [5], whilst miR-7a2 has been demonstrated to be essential for normal hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal function, with deletion in mice leading to cHH.

Administration of GH to the patient’s fibroblasts failed to produce the expected increase in IGF-I, leading the researchers to focus on the signalling pathways between these two molecules. This revealed a homozygous missense mutation in STAT5b, which rendered the protein incapable of activation by GH, despite being stably expressed.

Activated STAT5b in turn starts a signalling cascade that leads to increased transcription of IGF-I, IGF binding protein 3 and ALS. Together these molecules form a ternary complex, in which ALS stabilises the binding of IGF-I to IGF binding protein 3 and extends the half-life of circulating IGF-I. As the majority (80–85%) of IGF-I in the body is in this complex form, it was thought to be the main pathway through which GH exerts its effects.3

However, the case of a boy who entirely lacked ALS challenged this notion. The patient had a frameshift point mutation, which prevented production of ALS; he therefore had no ternary complexes and his plasma level of IGF-I was more than 5 SD below the average.

Yet, although the patient was referred to Horacio Domené (Ricardo Gutiérrez Children’s Hospital, Buenos Aires, Argentina) and colleagues partly for growth restriction, this was less severe than might be expected, at 2.05 SD below average. The team speculated that growth in their patient had been sustained by free or locally produced IGF-I, implying that total circulating IGF-I levels are less critical than previously believed.

Large-scale genome-wide association studies in the general population have highlighted hundreds of potential loci associated with the timing of puberty. Few genes at these loci have been shown to be causal in DP, although several loci are in or near to genes implicated in rare disorders of puberty (LEPR, GNRH1, KISS1 and TACR3) and pituitary function (POU1F1, TENM2 and LGR4), and two imprinted central precocious puberty genes (MKRN3 and DLK1). Genes involved in BMI control including FTO were also seen, and rare heterozygous variants in FTO have been identified in families with self-limited DP with extreme low BMI and maturational delay in growth.

Evidence for the role of the IGF-I receptor in pre- and postnatal growth came from Steven Chernausek (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Ohio, USA) and co-workers, who sequenced the gene in 51 children with heights more than 2 SD below average.5 They identified two children, who both had intrauterine and postnatal growth restriction and both had mutations in the IGF-I receptor gene, one resulting in reduced IGF-I receptor function and the other in a reduced number of IGF-I receptors on the fibroblasts.

Although closely related to IGF-I, and well-recognised as a major influence on intrauterine growth, IGF-II has been considered less important for postnatal growth. However, a very recent paper detailed how a paternally inherited IGF-II nonsense mutation resulted in Silver–Russell syndrome.6

Thomas Eggermann (University Hospital, Aachen, Germany) and co-researchers found their patients lacked mutations known to cause Silver–Russell syndrome, but detected the IGF-II mutation using exome and Sanger sequencing. Two of the three affected children were very small at birth but responded to later growth hormone treatment and achieved an adult height close to the third centile; the third did not respond and had continued poor growth.

Another aspect of these case studies was the finding of other, non-growth symptoms that the researchers attributed to the mutations in the GH/IGF-I axis, implying pleiotropic actions of this pathway. For example, the boy with truncated IGF-I had, among other symptoms, profound sensorineural deafness and mental retardation, the girl with mutated STAT5b had a compromised immune response, and the Silver–Russell patients had symptoms including severe postnatal feeding problems, delayed development, mental retardation and hypotonia.

Thus, the genetic basis of DP is highly heterogeneous, with gene defects producing pathogenic mechanisms that act from early foetal life into adolescence, all converging on a common pathway of pubertal delay.