Case history

A 6 years and 5-month-old female with Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) attends endocrine clinic with her mother. She was first seen by the endocrine team at 18 months old and the referral was made by a geneticist. Mum reports she has been obsessive and extremely challenging with her behaviour around food, and she is concerned about her child’s weight.

- Born small for gestational age at 34+6 weeks with a birth weight of 1.7 kg

- No initial concerns

- APGAR scores 9 and 9

- Ethnic minority heritage

- Postnatal hypotonia and feeding problems

- Genetics referral and confirmation of PWS in first year of life

- Community paediatrician services in place initially

- Reviewed by dietician around diagnosis

- Speech and language services in place

- Repeated chest infections from birth to 4 years

- Regular physiotherapy

- Sat firmly but unable to stand even with assistance at 2 years

- Started walking at 3 years

- Not initially interested in food when weaning

- One of two children

- Separate parent households

- Child’s mother works long variable hours

- Attended nursery full time prior to school

- The grandparents provide some child care

- She is in a mainstream school without an Education, Health and Care Plan in place

No community paediatrician periodically due to changes of home address.

Initial auxology:

| 18 months | Centile | |

|---|---|---|

| Height | 72.7 cm | <0.4th |

| Weight | 9.35 kg | 25th |

| BMI | 17.7 kg/m² | 75th–91st |

Initial investigations at 18 months included:

| Test | Value (normal range) |

|---|---|

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) | 4.13 mU/L (0.40–3.50) |

| Free thyroxine (FT4) | 9.3 pmol/L (10.7–21.8) |

| Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 level | 6 nmol/L (4.4–22.3) |

- Short synacthen test was carried out at 19 months to exclude central hypocortisolism. The child passed the short synacthen test with a peak cortisol of 590 nmol/L

- Possible TSH deficiency identified due to only mild elevation despite low level of FT4

- From 12 months, reported to eat fast and became distressed after finishing food

- Began eating meals with the family from age 18 months

Question 1.

Following the results of the initial consultation and investigations carried out at 18 months old, what treatment and monitoring plan would you initiate?

New diagnosis and support

The child and family had only received the diagnosis prior to attending the initial appointment. Therefore, discussion with the family around current guidelines and treatment options for children with PWS would be the primary focus.

The family should be encouraged to seek support information and services from a patient support group, in this case the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association UK (PWSA UK). Links to other national organisations can be found via the International Prader-Willi Syndrome Organisation.

Commence levothyroxine treatment

Due to the possible TSH deficiency, complete investigations such as a thyroid peroxidase antibodies test; then consider thyroxine treatment. This treatment can be reviewed again with regular monitoring.

A further trial off this treatment may be required depending on monitoring and symptoms when the child is older.

Physical examination

A complete physical examination is needed, including assessment for scoliosis despite the difficulties of assessing this in a very young child.

Ophthalmology Referral

An ophthalmology referral may be required for any signs of esotropia.

Growth hormone discussion

It is important to discuss the role of recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) therapy in the management of PWS, including the benefits, side effects and necessary monitoring required. It is recommended to be initiated before the onset of obesity, provided there are no comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and untreated severe obstructive sleep apnoea (Deal et al consensus guidelines, 2013).

The child is already 18 months old with a significantly high BMI.

High-quality evidence has shown the benefits of rhGH therapy for children at a young age with PWS; however, the links between rhGH and cognition have yet to be established and require further research (Passone et al, 2020).

Sleep study referral

The child would require a sleep study prior to commencing growth hormone therapy.

TFTs and IGF-1 blood tests

Monitoring of TFTs following initiation of levothyroxine and IGF-1 level prior to commencing any growth hormone therapy is needed.

Dietician referral

At 18 months the child is already displaying signs of hyperphagia. Despite initial feeding difficulties in infancy, the focus of any nutritional assessment should be based around ensuring nutritional needs are met within a significant calorie-reduced diet.

Psychology referral

It is important to consider the parental psychological and emotional adjustment to diagnosis.

Addressing weight gain: looking beyond patient factors

- Levothyroxine 25 µg once-daily medication commenced at 18 months.

- Growth hormone therapy was discussed.

- Sleep study satisfactory.

- Increased obsessive behaviours around food.

- Family were initially reluctant to initiate growth hormone therapy, and this continued through consultations.

- Declined dietetic referral due to commitments of attending more appointments.

- Psychology assessment appointment attended. Attendance for group support declined. Discharged from psychology services.

- Only dietetic support was initial contact prior to 12 months to maximise nutrition.

Key auxology changes:

| 18 months | Centile | 22 months | Centile | 2 yrs, 11 months | Centile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 72.7 cm | <3rd | 76.2 cm | <0.4th | 86.9 cm | 0.4th–2nd |

| Weight | 9.35 kg | >25th | 10.35 kg | 3-10th | 15.1 kg | 75th |

| BMI | 17.7 kg/m² | 75th | 17.8 kg/m² | 75th–91st | 20 kg/m² | 98–99.6th |

Question 2.

Reviewing further health and medical history as well as key auxology data from her early years, what observations would you consider to be significant in relation to her increasing weight and BMI?

Observations

- There has been a significant increase in the weight centile from the ages 22 months to 2 years 11 months; however, the child’s height has remained on lower centiles

Managing food intake

In order to improve both weight and body composition in children with PWS a reduced energy intake and well-balanced diet is required (Miller, et al, 2012). Forty percent of children and young people with PWS have been reported to be overweight or obese (Dien et al 2010), a prevalence which increases further into adulthood when studies have shown a range of 82–98% (Grugni, et al, 2011).

Children with PWS require approximately 60% of the energy requirements of a child of the same chronological age. It is extremely difficult, however, for the children and their families to address this reduced energy requirement at the same time when the child is unable to reach satiety.

The PWSA UK support group recommend that early intervention for dietary management and techniques are beneficial to the wellbeing of the child and become more difficult to implement as the child gets older.

Encouraging physical activity

PWS characteristics such as hypotonia may impair the ability to exercise and small feet creating balancing issues may further complicate physical activity.

A referral to the community paediatrician would ensure appropriate assessments are carried out in order to support movement and activity. An occupational therapy and podiatry assessment may be requested to address any daily physical challenges or any orthotic support the child may need.

- The parents have been unable to commit to additional hospital appointments for dietician-focused education

The focus initially would have been around optimising nutrition due to poor feeding when the child and family received dietetic support. There is a considerable shift of nutritional focus in the early years when physical challenges of safe feeding and early growth have been met, to when a nutritionally dense low-energy diet should be introduced.

This is a significant shift in thinking for parents especially if the child at this point may have a proportional weight and insignificant BMI.

No matter what age the energy-restricted, nutritionally dense diet is implemented, a regular dietetic assessment is necessary to monitor the nutritional status of the child. Energy restriction without nutritional assessments for dietary supplementation can potentially lead to nutritional deficits.

It is extremely rare to find a parent who is not able to see the benefits of professional guidance or who is unwilling to support their child by any means within their capabilities. However, the cost of attending multiple health and educational appointments can extend beyond the direct appointment time. Physical time, the impact on other family dependents and financial cost are widely recognised as barriers to patients accessing healthcare (Coumoundorous, et al 2019). In addition to these, psychosocial barriers such as low socioeconomic status and ethnicity contribute to poor patient outcomes (Paduch et al 2017). These findings would support any recommendations for co-ordinated, “one stop” systems of care for those children with such complex needs (Duis et al, 2019).

Ask direct questions, such as why is it difficult for the family to attend additional appointments. Exploring ways of overcoming these barriers by either providing the correct support or combining appointments should ensure the family have access to all the services they require.

- The child developed signs of hyperphagia at the age of 18 months, which have continued

There are currently phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials which are measuring the impact of medications on hyperphagia. However, to date no treatment has demonstrated a significant reduction in hyperphagia symptoms. And although these research trials are significant to the exploration of further treatments in PWS, they all exclude young children.

There are however management strategies such as a strict food routine, visual timetables and scheduled low-calorie snacks which are recommended to provide the child with a sense of food security.

A secure food routine along with the low-energy diet should aim to optimise nutrition and growth as well as minimise challenging behaviours around food. This aspect of care can be difficult for busy families to take on board and implement, but should be considered as early as possible and can even be beneficial at the point of weaning.

Dr Linda Goulash of the Pittsburgh partnership in 2016 identified some key strategies for parents to manage children’s expectations of food and minimise the behaviour problems often seen around food.

She talks of giving:

“NO DOUBTS about what will be provided and when it will be provided.

NO HOPE of obtaining food outside of the plan

NO DISAPPOINTMENT concerning the food”

- This child is part of a separate parent household

Moving between homes with different sets of house rules or guidance can also provide additional behavioural challenges (PWSA UK Behaviour information).

- The child’s parents have struggled with the initial diagnosis and have been unable to access further necessary psychological support therapies

It is well recognised that psychology services form an important part of the management of chronic conditions in order to help people identify and overcome barriers of managing complex health needs. For these reasons access to psychology services is mandatory and embedded in core healthcare services for other conditions such as diabetes mellitus.

- The time that the parents needed to adjust to the diagnosis has led to a delay in initiating growth hormone therapy and other management strategies

The inability to commence growth hormone therapy before the onset of obesity is also likely to have contributed to a lack of benefits seen by the treatment. For example, a decrease in BMI and higher lean body mass has been demonstrated in patients with PWS who start growth hormone at a young age (Passone, 2020).

Proactive management: anticipating the biggest challenges

Each child, young person and adult with PWS will have individual needs; however, there are some known common characteristics of PWS.

Question 3.

Thinking about this patient at 6 years and 5 months, which of the following common characteristics of PWS would be of particular concern for yourself and the family?

- Hypotonia

- Hyperphagia

- High pain threshold

- Ineffective or non-existent gag reflex

- Scoliosis

- Hypogonadism

- Early adrenarche

- Inability to regulate temperature/altered temperature sensitivity

- Skin picking

- Speech articulation problems

- Esotropia

- Intellectual disability/learning difficulties and associated emotional developmental delay

- Obsessive compulsiveness/obsessional traits

Hypotonia

The presence of hypotonia may contribute to increases in weight and inactivity. Addressing hypotonia through rhGH and physiotherapy can also allow the family to use movement and activity as distraction techniques for managing obsessive behaviours.

Hyperphagia

This characteristic can lead to weight gain and subsequent obesity. Associated complications of obesity would be a major current concern as well as for the future health of the child.

Ineffective or non-existent gag reflex

As a common characteristic of PWS coupled with symptoms of hyperphagia an ineffective or non-existent gag reflex can increase choking risks. When consuming food, supervision and encouragement to chew the food is advised.

Speech articulation problems

Physiological characteristics such as a high arched palate, low muscle tone and learning difficulties can lead to communication difficulties and frustrations with communication which may exacerbate challenging behaviour, particularly if verbal comprehension skills exceed verbal expressive skills.

Intellectual disability/learning difficulties and associated emotional developmental delay

Learning and emotional difficulties can impact the behavioural challenges displayed by any children and would not necessarily be linked to the intellectual level of the individual child.

Some of the common characteristics linked with PWS such as short-term memory difficulties, speech and language difficulties, inability to process spoken information, lack of abstract thinking and immature emotional development can lead to emotional fluctuations in mood which occur at any time. Changes in moods can be seen particularly with changes of routine, transitioning from one thing to another or a lack of food security.

Cultural, social, educational, parental and carer’s attitudes towards addressing these difficulties all have an impact upon whether the child is likely to reach their full health, wellbeing and educational potential.

The child does not have an Education, Health and Care Plan in place which would be highly recommended. In the meantime, encouraging those around the child to see and treat the child as their presenting emotional age rather than their chronological age would encourage improved communication and more tailored learning opportunities until an Education, Health and Care Plan is established.

Positive ways for parent and school staff to address challenges with learning and challenging behaviours can be found (PWSA UK education and skills information).

Obsessive compulsiveness/obsessional traits

Obsessive compulsiveness can be difficult to manage if it is targeted at a particular object or person. In children of this age who have PWS, this often manifests as habitual and repetitive discussions of one topic, which can be very mild or become excessive. Quite often a topic of interest is food and, due to the inability to reach satiety, this can be the most challenging day-to-day aspect of supporting a child with PWS.

Question 4.

As part of your consultation there are two other external factors which may impact on the family’s abilities to support the child’s behaviour, food and weight gain challenges.

Why do you think each of these other factors may be having an impact?

- Consistency of community paediatrician services

- Parental carer’s fatigue

- Family functioning and sibling dynamics

- Consistency of community paediatrician services

Imperative to a child reaching their full health and educational potential is a co-ordinated approach to support (Duis et al, 2019). The community paediatrician is in a prime position to facilitate such co-ordination as they bridge the gap between both primary and secondary health and educational services. This does not negate the importance of each individual health and educational service; rather it stresses the need for co-ordinating multiple services for the benefit of the child’s health and wellbeing.

- Parental/carer’s fatigue

Obsessive questioning, particularly around food and the challenging behaviours described by the mother are typical characteristics of PWS but can lead to parental/carer’s fatigue.

Parental/carer’s fatigue is also known as compassion fatigue and has been described as the daily stress of parenting which becomes chronic leading to a disconnection with the child and therefore an inability to meet any more than their basic physical needs.

Parental/carer’s fatigue is usually brought about by trying to meet additional needs and behavioural challenges. It results in physiological changes in the parent’s brain rendering the parent/carer unable to access empathy or the brain’s cortex-based thinking (Hughes D and Baylins J, 2012).

Signs of parental burnout such as feelings of isolation, emotional detachment, worthlessness or ineffectiveness have been reported to have lasting consequences for both children and parents (Ottoway & Selwyn 2016). Therefore, in the face of addressing complex health, educational and behavioural challenges seen with parenting a child with PWS, parenting capacity needs to be equally addressed with an empathic approach as part of the child’s ongoing care.

Strategies such as a “brain break” – anything from 10 minutes to 2 weeks – and access to an empathic listener or to those experiencing similar challenges can help parents recognise and address any potential parental/carer’s fatigue. Lots of recommendations for change by well-meaning professionals often go unheard by parents when they are experiencing parental/carer’s fatigue (Naish, S. 2018).

Access to support networks such as the PWSA UK and embedding psychological services for early and ongoing interventions will benefit the family’s abilities to process the diagnosis and build resilience for the day-to-day management in some of the more challenging characteristics of PWS.

It is important that parents don’t feel that when they are accessing this support that they have failed in any way. These supportive services should be presented as standard aspects of care.

- Family functioning and sibling dynamics

Parents of children with PWS report a perceived poorer quality of life following increased family conflicts and difficulties with communication and functioning, compared with parents caring for children with other complex health needs (Mazaheri et al, 2013). Mazaheri also reported that 92% of siblings have demonstrated moderate to severe symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome when being reared with a sibling who has PWS.

Work published by the PWSA USA has described two roles siblings of children with PWS can take on, and the impact these roles can have on their well-being and the family dynamics. One is a nurturing role, which can leave a sibling missing out on life experiences and feeling guilty if they are not supporting the child with PWS and the family. The second role is a triggering relationship whereby the sibling is resentful of the impact on the family and can antagonise the child with PWS and therefore increase the tensions experienced within a family.

Ongoing monitoring and role of growth hormone therapy

Growth hormone therapy was finally introduced at 3 years 10 months. With a body surface area of 0.77 m² the child was initiated on 0.2 mg once daily, based on the hospital guidelines starting dose of 0.25–0.5 mg/m² per day or 9–15 µg/kg per day. This dose was then gradually increased following monitoring over a period of 3–6 months to the recommended dose of 1.0 mg/m² per day or 35 µg/kg per day (with a maximum of 2.7 mg daily) for PWS (NICE, 2010).

| 2yrs 11 months | Centile | 3yrs 10months | Centile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 86.9 cm | 0.4–2nd | 97.5 cm | 9–25th |

| Weight | 15.1 kg | 75th | 19.1 kg | 91st |

| BMI | 20 kg/m² | 98–99.6th | 20 kg/m² | 98–99.6th |

Growth hormone was then stopped due to a failed sleep study, conducted after obstructive breathing and snoring overnight was reported. Grade 2–3 tonsils and patent nasal airway were noted at 5 years 11 months and subsequent diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea confirmed.

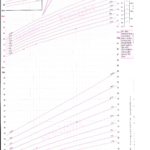

Growth and weight chart for girls aged 1–4 years (click to view):

Question 5.

The child is now 6 years 5 months. What investigations under the following headings if any would you need in order to address the main presenting concerns in clinic?

- MEASUREMENTS

- PATIENT QUESTIONNING

- BLOOD TESTS

MEASUREMENTS

Weight (kg) (centile) standard deviation score (SDS)

Height (cm) (centile) SDS

BMI (centile) SDS

Blood Pressure

Height velocity (centile) SDS

Weight velocity (centile) SDS

These measurements would help to assist an assessment of the child’s current obesity status and therefore potential obesity risk factors.

PATIENT QUESTIONING

- Diet history/food routine/food security/food-seeking behaviours

Get a picture of how often the child is eating, as well as portion sizes and what food routines or boundaries the family have in place. Further advice or re-referral to the dietician may be necessary. Understanding if there are persistent or escalating food-seeking behaviours, and in what environment they are occurring (eg, school or home), can help direct the endocrine specialist towards different support services in order to address the child and family’s individual needs.

- Scoliosis assessment

This is considered a routine aspect of care and of particular relevance as the child has been on growth hormone therapy.

- Otolaryngology questions/sleep study results

It would be imperative to address any compromised airway symptoms by stopping growth hormone therapy immediately and making an urgent referral to the appropriate respiratory team. Therefore, regular routine questioning around symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea is essential.

- Check Educational Health Care Plan status

Considered discussions around appropriate school placements to meet the child’s needs can be addressed through the Educational Health Care Plan channels.

BLOOD TESTS

- TFTs

- Liver function tests (LFTs)

- Lipid profile

- Glycated haemoglobin

- Blood glucose

- IGF-1

IGF-1 levels repeated 12-weekly during the first year of treatment and 6–12 monthly thereafter.

Additional blood screening for the co-morbidities of obesity would be required. An ultrasound scan of the liver may be necessary if the LFTs are abnormal.

Cortisol levels may be added if there are clinical concerns of adrenal insufficiency

An adenotonsillectomy was carried out at 6 years and a repeat sleep study following the adenotonsillectomy was reported to be normalised.

At 6 years 5 months:

No advancement of mild scoliosis was reported.

TSH and IGF-1 levels within expected range

| 3yrs 10 months | Centile | 6yrs 5months | Centile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 97.5 cm | 9–25th | 116 cm | 25–50th |

| Weight | 19.1 kg | 91st | 39.35 kg | >99.6th |

| BMI | 20 kg/m² | 98–99.6th | 29.2 kg/m² | >99.6th; +4.08 SDS |

Body surface area 1.3 m² (NICE, eBNFC, 2019-2020)

Growth and weight chart for girls aged 2–8 years (click to view):

Question 6.

Knowing the results of the normalised sleep study would you now restart growth hormone therapy?

Yes

Question 7.

When deciding to restart growth hormone therapy what dose would you initiate? (For body surface area=1.3 m2; 6 possible answers)

- 0.3 mg – once daily

- 0.35 mg – once daily

- 0.4 mg – once daily

- 0.45 mg – once daily

- 0.5 mg – once daily

- 0.55 mg – once daily

- 0.6 mg – once daily

- 0.65 mg – once daily

The doses highlighted demonstrate a therapeutic range for commencing growth hormone therapy.

Taking into consideration the patient’s previous history and growth hormone delivery device the patient was restarted on 0.4 mg once daily growth hormone. A dose of approximately 0.5 mg/m² per day or 12 µg/kg per day and close monitoring were established. Utilising body surface area can prevent an inappropriately large dose of growth hormone based on a child’s excessive weight.

Question 8.

Additional to the monitoring you have already established in the consultation (Question 5) what further patient monitoring would be beneficial to assessing a child receiving growth hormone therapy?

- Sleep Study

Sleep study 8–12 weeks after restarting growth hormone and annually thereafter.

Consider possibility of additional sleep studies if a compromised airway is suspected.

- Growth hormone and side effects

Check injection technique, or if the parent and child are experiencing difficulties around the growth hormone injections.

Scoliosis should be monitored for signs of worsening.

Discussion and questioning around signs and symptoms of growth hormone side effects would be highly recommended.

- Blood test

Glycated haemoglobin, blood glucose and IGF-1 have already formed part of your general assessment and obesity comorbidity screening; however, a repeat IGF-1 in conjunction with the repeat sleep study at 8–12 weeks is also necessary.

IGF-1 levels should be considered in the context of potential excess growth hormone signs such as hypertension, poor glycaemic control and presence of an obstructed airway.

- Collaboration of multidisciplinary team and patient-centred care

A co-ordinated multidisciplinary approach to communicating and meeting the needs of the child and family should be the primary focus of any care and educational interventions. These collaborative interventions are required to span across primary, secondary and community settings in order to help this child reach their full potential in terms of both clinical and educational outcomes (Duis et al, 2019).

Finding new ways of supporting children and young people with complex health needs and communicating with each other remotely has never been so easy and is likely to remain embedded in new ways of providing health care services.

- Transition

The transitioning of the child with emerging and increasingly complex needs to adult services will require careful planning and time between the family, the services currently in place and potential services available at the time of transitioning.

Bridges N. What is the value of growth hormone therapy in Prader Willi syndrome? Arch Dis Child 2014; 99: 166–170

Carrel AL, Myers SE, Whitman BY, et al. Growth hormone improves body composition, fat utilization, physical strength and agility, and growth in Prader-Willi syndrome: a controlled study. J Pediatr 1999; 134: 215–221

Lindgren AC, Hagenäs L, Müller J, et al. Growth hormone treatment of children with Prader-Willi syndrome affects linear growth and body composition favourably. Acta Paediatr 1998; 87: 28–31

Miller JL. Approach to the child with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: 3837–3844

Passone CBG, Pasqualucci PL, Franco RR, et al. Prader-Willi syndrome: What is the general pediatrician supposed to do? – A review. Rev Paul Pediatr 2018; 36: 345–352

Sinnema M, Maaskant MA, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk HM, et al. Physical health problems in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2011; 155: 2112–2124